Posts Tagged ‘Winter Shelter’

Good news for Columbia’s homeless: Catholic Charities of the Midlands will open a free shower and laundry facility downtown Monday, March 7, right across the street from the city’s bus transit center. As you can imagine, sometimes a hot shower and clean clothes can make all the difference when you’re on the streets.

It’s filling a need. There are no coin laundries in downtown Columbia, and few opportunities to take a free shower, so a lot of people end up taking “bird baths” in a bathroom sink at places like the Richland County Public Library.

Chuck Waters, a homeless man who’s part of the Homeless Helping Homeless advocacy group, told me that once the Winter Shelter closes April 1, “you’re not going to have a place to shower unless you use a hose or go to the river.”

The facility, called Clean of Heart, will only be able to serve about 30 people a week to start, and you’ll have to sign up in advance at Catholic Charities, but, in the words of one of the organizers, “It’s 30 more than right now have access.”

Read the rest in an article I wrote for the Carolina Reporter.

Among my glaring character flaws: I’m terrible at keeping up with friends.

Matt and I made some close friends during our three days on the streets, and I want to do a better job than usual of not losing track of them. This post is about that.

Ernest, Dawn, Tommy, and John were our indispensable Sherpa guides. They showed us where to sleep, taught us how to walk and talk and argue, and introduced us to kind souls while steering us clear of the crooks and mouthwash drinkers.

I’m hard-pressed to think of a time when I’ve been more dependent on someone for safety. Maybe that’s why homeless people are often so choosy with their friends: Befriend the wrong person and you’re endangering yourself. Friendships among homeless people seem to be less based on common interests and more based on the idea that a person will protect and stick up for you, maybe even lay down his life for you.

I sat down with Tommy for dinner Monday night, and he got all emotional with me, talking about the serendipity of our paths having crossed and the firmness of his conviction that we would always be linked. It was the sort of conversation that men rarely share, and when we shook hands goodbye, I knew it was something sacred.

The next evening, I got a call from Ernest, who had me on speakerphone so I could hear Dawn as she thrashed him in a game of rummy.

Back on March 31, the day before the Winter Shelter closed, I gave the two of them a ride to the Greyhound station and sent them on their way with a bag full of sandwiches and apples and a calling card — all the things I thought my mom would have handed me. Ernest had secured jobs for both of them, along with a friend, in a traveling carnival based out of Indiana. As we pulled into the parking lot, someone was singing Leonard Cohen on the radio:

“Love is not a victory march;

It’s a cold and it’s a broken hallelujah.”

It was a tough departure for Dawn, and while some of this had to do with the fact that she’d never left the state before, it was mainly because she was leaving her children behind.

Dawn’s got three kids, and she knows that no court will award her custody while she’s homeless. The plan is to save up her money until the carnival ends in October and then come back to collect her children. She said she hopes they’ll understand one day why she has to do this.

As for Tommy and John, they cleared out of their downtown sleeping spots once the Winter Shelter closed, hoping to avoid confrontations by setting up camp in the woods. So far so good, but tensions are high. John’s been talking about some bad blood among their group of friends, and Tommy, a recovering alcoholic, has decided he can’t be around his longtime friends who drink liquor every night.

Still, Tommy was in higher spirits Monday night than I’d ever seen him. He’d spent some considerable time sitting by the river alone, playing his guitar and watching the water pass, and he spoke euphorically about Heaven and the promise that all things will be made new. I could tell he’d been praying a lot, and he said he’d been praying for me.

Tommy talked plans: He wants to start a homeless Bible study, and he said he’s got around 25 people interested in it on either Monday, Tuesday, or Wednesday nights. He asked me to see if any college ministries wanted to help out.

He told me that, once he finally gets things straight with Veterans Affairs and receives his five years’ worth of checks in arrears, he’ll put most of the money in the bank, buy some good boots and a tent, and hike the Appalachian Trail, living off the land and the kindness of strangers. Upon returning, he’ll find a place of his own and continue the job hunt.

I asked if I could tag along once again, and he said that would be fine.

Columbia’s Winter Shelter closed for the spring Thursday morning, sending hundreds of the city’s homeless back outside at nights.

“250 people are headed nowhere,” said Billy, a 56-year-old homeless man who’d been staying at the Winter Shelter. The shelter’s exact capacity is 240, but the fact remains: Living arrangements are up in the air.

Billy, who withheld his last name, listed the same potential sleeping spots as many others facing the same predicament: parking garages, abandoned houses, the woods. If there is an unoccupied nook or cranny downtown, odds are the homeless scoped it out Thursday night.

Cooperative Ministries Executive Director David Kunz, whose organization helps fund the Winter Shelter, said there will not be enough beds in other area shelters to absorb the 240 homeless who left Thursday morning.

“The good majority of them will be sleeping outside,” Kunz said.

This happens every year. The shelter won’t reopen until October, so downtown residents and business owners will have an increased number of outdoor neighbors throughout the warmer months.

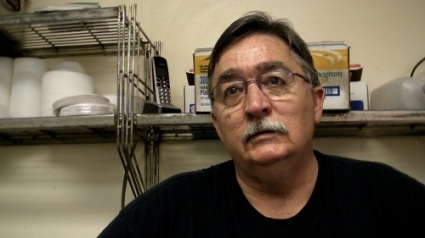

Steve Rowland, owner of Drake’s Duck-In on Main Street, said his problems are about to multiply: panhandling during lunch hours, drunken confrontations with customers, defecation and urination in front of his store at night. He’s owned the restaurant for 40 years, and he says he knows people who have been homeless that entire time and made no attempts at getting jobs.

“I didn’t inherit the responsibility for these irresponsible people,” Rowland said. Every morning, he has police escort his manager into the store in case someone is sleeping on the front porch again.

Dorothy Thompson, who runs T.O. Thompson Jewelry Repair with her husband Harold, said she’s more concerned about prisoners being let off at a nearby bus stop than about the homeless, whom she sees as mostly harmless and in need. Still, she said she had to put up a chain-link fence last summer to keep people from sleeping on the stairs behind the store.

Is it safe to go downtown at night? Columbia Police Chief Tandy Carter said that only 2 or 3 percent of Columbia’s homeless are criminals, and that they tend to commit more property crimes — specifically auto break-ins — than violent crimes.

“Homelessness is a public health concern, not a police concern,” Carter said. “The enforcement end, to us, is not as important as trying to line them up with the right services.”

What if the Winter Shelter were kept open year-round? Certainly, some people would get complacent and learn to call it home.

But for the ones who are still trying, a shelter is a chance to save money. Here’s a common scenario: A man stays in the Oliver Gospel Mission’s transient dorm for 30 days, at which point shelter policy dictates he has to leave for 14 days so his bed can be offered to someone else. For those first 30 days, he has no housing costs and can save his money toward more permanent living arrangements.

For the 14 days outside the mission, though, he can either live on the streets for free — and run the risk of being robbed in his sleep or arrested for urban camping — or he can check into a hotel room. He chooses the hotel.

Say the man pays $40 a night at the hotel. Over 14 days, that costs him $560. In other words, he’s paying a month’s worth of apartment rent for half a month in a hotel. So much for savings.

When it comes to nighttime on the streets, one thing is different this year: the Clean and Safety Team. Funded by private donations and a special tax on downtown businesses, these goldenrod-clad guards patrol the downtown area. Their job is broad-ranging, but part of it is to move homeless people along when they’re caught sleeping downtown.

Until recently, the yellowshirts (as they are nicknamed) would call it quits around 11:30 p.m. Homeless people knew this, and they waited until then to lie down.

Now, the yellowshirts have a third shift that goes late into the night. There are two ways to look at this:

- The streets will be safer at night. Daniel Long, the team’s homeless outreach coordinator, called the yellowshirts “the eyes and ears of law enforcement” and said they’ve helped solve several crimes downtown with the cooperation of the homeless.

- Things might get ugly at night. For some, like my homeless friend Tommy Capps, the late-night shift means it’s hard to get any sleep. When I stayed outside with him one night, we got to sleep around 11:30 p.m. and woke up at 4 a.m. For a few days after the night shift began, Tommy got almost no sleep.

Tommy has expressed concern about the volatile mix of persistent yellowshirts and tired, frustrated street sleepers. Tommy is himself non-confrontational and carries no weapons, but all it would take is one belligerent homeless person to turn things awry.

“One of them could make 20 of us look bad,” Tommy said.